Gravitational waves

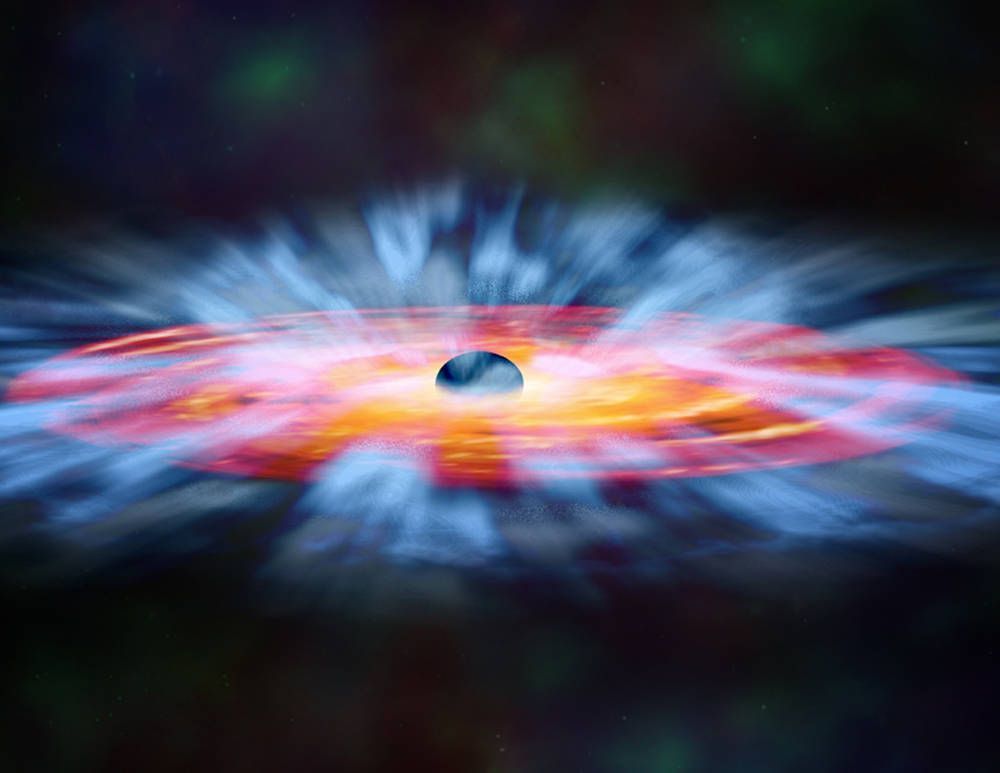

Gravitational waves transmit gravitational force or the force of attraction. When an object moves, it triggers a gravitational wave, making the change in gravitational pull perceptible to other objects. It can be something as small as a spoon falling to the ground or something gigantic, like two black holes colliding. Naturally enough, colliding black holes alter gravity more than a spoon falling to the ground, as they have a much greater mass.

The assumption that gravitational waves exist emerged at the beginning of the 20th century. The general theory of relativity states, among other things, that nothing can travel faster than light. Consequently, changes in gravity cannot be faster than light. Until then, however, researchers had assumed that gravitational changes were immediately noticeable without any time delay. Gravitational waves would explain how changes in gravity propagate without questioning the speed of light as the maximum speed.

First detected in 2016

In 2016, researchers from the LIGO Collaboration (Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory Collaboration) - see box on right - reported for the first time that, in the autumn of 2015, they had measured such gravitational waves which were actually generated by a collision between two black holes.